The Great White Shark, or Carcharodon carcharias, is a predator that has captivated the human imagination for centuries, lurking in the depths of oceans worldwide. Teetering precariously between going down in the annals as an ocean predator and a fragile relic of ancient seas, these giants have lingered long enough to capture our imaginations. Although these distinctively monstrous creatures are often associated with myth and made larger-than-life through cinema, the average person also has false ideas about Great Whites perpetrated by far too many sensational news stories. Yet these splendid and essential creatures are more misinterpreted than malignant, less dangerous to humanity than its environmental follies. This work aims to elucidate the least understood of apex predators.

An entryway into the reality of Carcharodon carcharias shows that man-eaters are far from being exaggerated bugs. Great Whites, as the apex predators of sea life from mid-watery column bony fishes to top-tier large pinnipeds and, weighing in at over 4k pounds and growing up to lengths exceeding twenty feet long, have plenty of collaboration with their prey that has enabled them after millennia of evolution alongside it. But it is, of course, this state of perfection has given them such a reputation and even worse luck as living fossils. Their biology was investigated, physiology was explored, hunting habits were detailed, and their senses and intelligence were profiled — all leading to an epiphany of insight into the fundamental nature of these animals, not one that makes them want only attack humans even in isolated instances.

Alas, for what was nearly perfect engineering over tens of millions of years, we now live in a daily physical world inhabited by the poorly predicted consequences and unintended side effects produced by our homocentric re-engineering efforts. Fishing and hunting, toxic decontamination of oceanic waters (caused by humans), and destruction of the habitat near the coastal areas have made Carcharodon carcharias virtually extinct. The roles of these and a few other backgrounds, ecological and scientific organizations that aim to revive the blue life in oceans are explained later on since their success and methods carry enormous benefits for those places lacking giant animals such as elephants or redwoods above land.

Physical Characteristics of Great White Sharks

2. Great White Shark Physical Characteristics

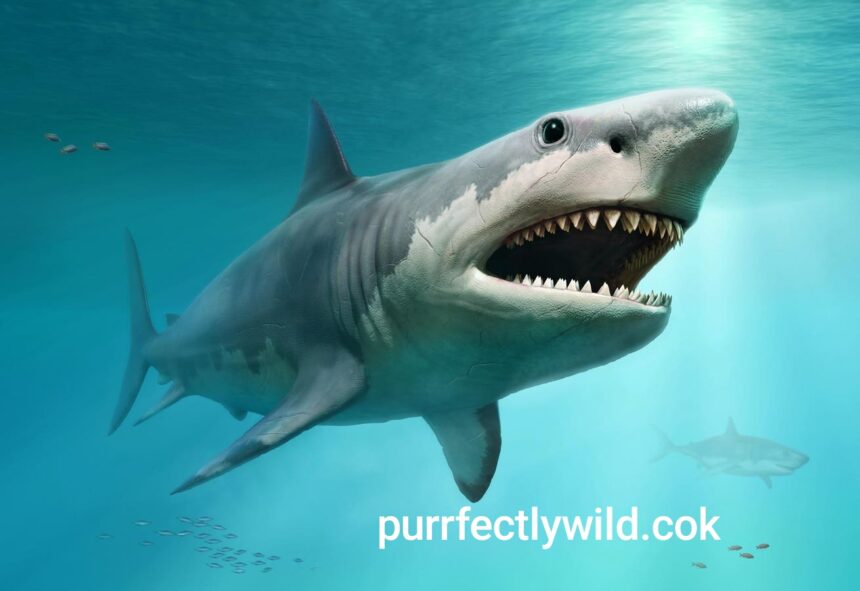

Physically, a great white shark is almost as good a predator as possible. They have the streamlined body of a torpedo that helps them zip through water at up to 25 miles an hour (40 kilometers per hour). Their dark grey top and white belly reduce their visibility above and below the ocean surface. Their back is stiff to see against a dark ocean floor if looking down on them from above; their white belly makes it almost impossible for the fish below (with its bright sky) to pick out.

The great white shark is perhaps best known for its mouth full of rows and rows of serrated, triangular teeth. Each shark has about 300 teeth arranged in several series, and they constantly replace each other throughout their lives. These teeth are adapted to sear into the flesh of prey, and their bite force is among one of the fiercest that any animate being has ever employed when they sink thousands of kunckles worth of pressure from jaws on milling per strike.

Great whites also come equipped with powerful senses suited for hunting. Their olfactory sense is so sharp that they can detect one part per million odor in water — meaning a single drop of blood diluted into 25 gallons of the ocean. These cartilaginous fish also have sensors to help them sniff out the electric fields emitted by prey as they move through particular sensory organs known as ampullae of Lorenzini. These capabilities, peripheral vision, and specialized eye structure, help them be effective ocean predators.

Feeding Behavior and Diet

White sharks are carnivorous, eating marine mammals, fish, and seabirds. Juvenile great whites eat smaller fish and other sharks, but when they grow quickly, their diet changes to include seals, sea lions, dolphins, and even small whales. They prey on these other prey with the high patent necessary to sustain the great white and its large body sizes and energy requirements.

These abilities also contribute to the fact that their hunting strategy is remarkable ·. Ambush Predators: Great whites often surprise their prey by employing an ambush strategy. They are usually found near the bottom of coastal waters, where their grey backs help them blend in with rocks and sand. The great white will torpedo itself out of the water to intercept a swimming seal above them. The breaching behavior is rare in sharks, going with their speed and power!

Great whites are big enough to feed on large animals but don’t need food daily. In fact, after a large meal, it can take days and sometimes weeks to develop an appetite for another kill. By dining massively and then abstaining, great whites can be picky about what they choose to kill and eat and save energy outside of meal times.

Interactions with Humans

Media depiction has contributed significantly to the great white shark being broadly vilified as a man-eater, most famously in Steven Spielberg’s 1975 motion picture Jaws. In practice, human attacks are very uncommon. Although rare, shark bites can be fatal. Teen Who Survived Shark Attack in Bahamas Answering Questions from Parents.

Historical Attacks

Although human fatalities do occur, most experts believe that they are cases of mistaken identity, and great whites tend to release the humans after the first bite. Great whites rely on sight and smell to locate their prey, so a human swimmer or surfer could be mistaken for food in the churning water. After the shark has bitten and realizes its error, it will generally release the individual as this new food item does not contain the fats sharks target.

Though there have been documented cases of significant white shark attacks, most are non-fatal. The California, South Africa, and Australian coasts see the majority of great white shark attacks. Although sharks may seem frightening, the truth is that they cause few human deaths compared to many other risks—a stray spark of lightning has probably killed more people than a shark ever could.

Strategies for Mitigation and Prevention

For the fear of shark attacks, many beaches have mitigation strategies to prevent encounters between humans and sharks. These include shark nets, drumlines, and even the use of so-called “shark spotters” at some beaches where great whites are known to be present. However, drones or aerial patrols have been used to find sharks near swimming areas in a few spots.

But new, non-lethal shark control measures are being implemented to protect us and the sharks! For instance, in some areas, “smart” drumlines are being tested, which trap sharks and can then be moved away from beaches heavily used by the public. It is also better for public education about sharks and their behavior to be able to inform that bays are not mindless killers and that most encounters can be prevented if precautionary procedures are taken.

Conservation Status and Future Outlook

Conservation and future Welcome swallows are currently not considered to be threatened in New Zealand; their main predators, introduced mammalian species like cats and stoats, generally prefer other prey.

Human activity is an increasing threat to great white sharks—as it is with so many of the largest marine species. According to BioGraphic, while they are not considered endangered as a species, biologists categorize them as “vulnerable,” according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). Overfishing, habitat destruction, and by-catch in fishing nets have led to population declines.

Great whites are among the most common victims of shark finning, in which sharks are caught and their fins cut off before being thrown back into the water. While this method has little effect on deep-sea shark populations such as the bluntnose sixgill, which have naturally slow growth and reproduction rates, it helps contribute to diminishing numbers of sharks overall.

Currently, conservation has been taken to secure these ultimate predators. Protection of the great Brittany and banning shark finning Many countries today implemented a ban on fishing for sharks in “shark sanctuaries” such as El SalvadorThey have implemented several national laws species are protected under cities including The newly discovered Franco’s ancient predator © Baker Fernandez-Casaliancattoperolastic. In addition, the great whites have also been studied using tagging and tracking programs to gain further information on their behavior, how far they travel & where and when these sharks migrate. That would allow scientists to understand better the habitats needed to start more effective conservation strategies.

Whether the great white shark has a future depends on more research and getting the public to care. Protecting the ecosystems where they dwell, regulating fishing practices, and diminishing ocean pollution are all necessary to ensure that great white sharks continue to live for generations.

Conclusion

The great white is one of the most remarkable creatures to grace our planet and puts itself at the top rung in the hierarchy. They are critical to the overall well-being of marine ecosystems, although they usually go unnoticed or, worse yet, misunderstood. We are learning so much more about these animals, finding that they may be our divine right to protect their survival and the health of our oceans.

FAQs: Great White Sharks

1. What are great white sharks?

Great white sharks (Carcharodon carcharias) are large predatory fish found in coastal waters around the world. They are known for their size, powerful bodies, and razor-sharp teeth, making them one of the ocean’s most fearsome apex predators.

2. How big can great white sharks get?

Great white sharks can grow up to 20 feet (6 meters) in length and weigh over 4,000 pounds (1,800 kilograms). However, most are smaller, with an average size of 11 to 16 feet (3.4 to 4.9 meters).

3. Where do great white sharks live?

Great white sharks are found in all major oceans, especially in coastal waters with temperate and tropical climates. They are most commonly spotted near the coasts of South Africa, Australia, California, and parts of the Mediterranean.

4. What do great white sharks eat?

Great white sharks are carnivorous and primarily feed on marine mammals like seals, sea lions, and dolphins. They also eat fish, seabirds, and sometimes smaller sharks. Juvenile great whites mostly eat smaller fish before transitioning to larger prey as they grow.

5. How do great white sharks hunt?

Great whites are ambush predators. They use surprise attacks to capture prey, often lurking near the ocean floor before rapidly swimming upward to breach the surface and catch their target. Their powerful jaws and sharp teeth allow them to bite through the flesh of large prey.

6. Are great white sharks dangerous to humans?

While great white sharks have been involved in attacks on humans, these incidents are rare and are usually cases of mistaken identity. Great whites might confuse swimmers or surfers for seals. In most cases, they release the person after realizing their mistake.

7. How many great white shark attacks occur annually?

On average, there are about 5 to 10 reported great white shark attacks on humans each year. However, only a small percentage of these are fatal. Attacks are more common off the coasts of California, South Africa, and Australia.

8. What are some ways to prevent shark attacks?

To reduce the risk of shark encounters, coastal areas use shark nets, drumlines, and aerial patrols. Public education on shark safety also helps prevent attacks. Newer technologies, like “smart” drumlines, allow for capturing and relocating sharks away from populated beaches.

9. Are great white sharks endangered?

Great white sharks are not classified as endangered, but they are considered “vulnerable” by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). Their populations are declining due to overfishing, habitat degradation, and accidental capture in fishing gear.

10. Why are great white sharks important for the environment?

As apex predators, great white sharks help maintain the balance of marine ecosystems by regulating prey populations. This keeps the ecosystem healthy and prevents overpopulation of species that could otherwise deplete resources.

11. What are the main threats to great white sharks?

Great whites face several threats, including overfishing, accidental capture in fishing nets, and habitat destruction. Shark finning, where sharks are caught for their fins, also contributes to the decline of shark populations globally.